One day the sommelier and I hiked to nearby Sujata Temple. The story goes that the prince Siddhartha Gautama, later to be known as the Buddha, had been practicing austerities with a band of ascetics. He had been meditating in caves and eating only “the grains of rice that fell into his mouth.” This is a period of his development that is often depicted in Buddhist art and imagery as “the skeletal Buddha.” Realizing that he was waisting away to nothing but skin and bones he decided to stop. He was ridiculed by his fellow ascetics for leaving the path of their extreme disciplines. Siddhartha then came down through this area of the Indus river valley and was offered rice-milk (and some think something else) by the princess Sujata. Soon after he resolved to sit under the bodhi tree until the nature of life and reality had become clear to him.

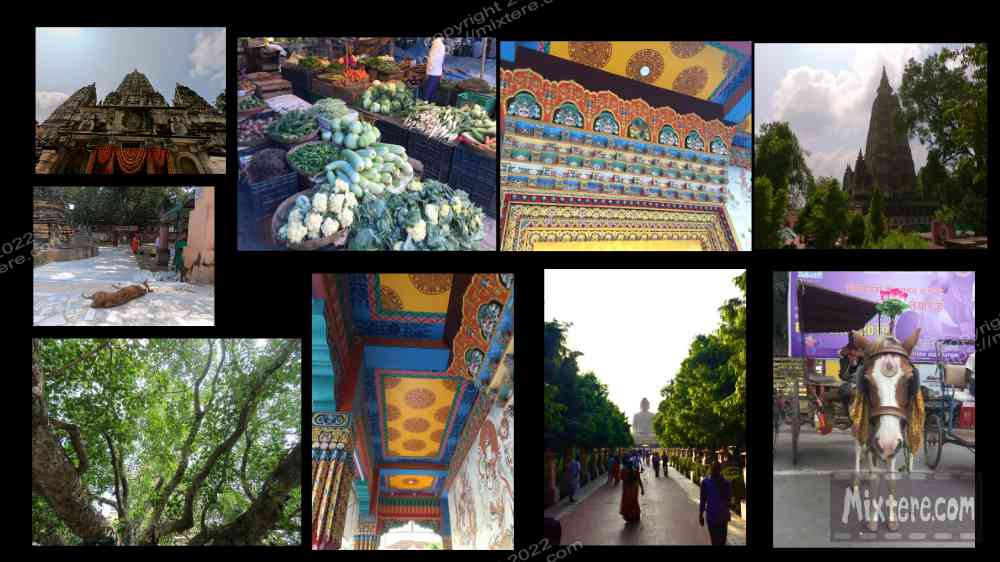

The site of the Buddha’s pit stop was the destination of our hike. Since arriving in Bodh Gaya I had begun to resent the constant pressure from people to hustle money from me. This experience robs one of the experience of being able to go about freely without being part of some hustler’s scheme. I figured a walk in the country would be a break from this. The sommelier and I left the guesthouse using my phone’s map for navigation help. I was thrilled to be able to freely and independently direct myself on the hike. Alas, within two minutes a local attached himself to us as a “guide” and persisted all the way through the village to the temple. We politely ignored him and he in turn ignored our refusal of his services. During our walk we were offered quite a window into poor Bihari villager life. I noted the somewhat freeform mason work, the nearness of agriculture and the plethora of dogs, cows, water-buffalo and goats wandering about or tied in their pens.

Patties of dung mixed with straw were plastered everywhere, even on the tree trunks, for the sun to dry. With little firewood or coal, the dung patties were the villagers’ fuel to cook with.It felt free to be away from the noise of the streets, the masses of people, exhaust, smoke and road-dust of Bodh Gaya. With the exception of our annoying guide, peace pervaded the village and the countryside surrounding us. Verdant green rice fields extended out in every direction. We turned a corner and came upon a large male water buffalo. Unfortunately I had chosen to wear a red shirt and I noticed him looking increasingly anxious as I approached. I don’t know if there is anything to the belief that bulls are instigated by the color red but I definitely didn’t want to find out. Thankfully he let us pass.

We eventually made it to the temple. A large Chinese tourist bus was parked outside which to me was not a great sign. We walked through the temple grounds while our self-appointed guide insisted to appear to be leading us. We continued ignoring him and chose to rest in the shade of a large tree next to a stupa. Despite our attempt to keep a low-profile the solicitations for money and services came constantly. A man who claimed to run the temple’s school stepped up to us. Upon learning that I had been a teacher he urged me, on the spot, to please enter the building and begin teaching the children. “Why did I open my big mouth?!” I told myself as I calmly and repeatedly declined the offer. I attempted to visibly redirect my attention to the rice fields waving in the breeze. Well, the flow of solicitations were not letting up so the sommelier and I decided to leave. We dodged the last of the hustlers and forcefully bade a final farewell to our insistent guide.

It was a relief to be walking on our own again. We walked on the road for a while and then veered off onto a dirt path. There was a remote stupa a considerable distance into the rice fields and we established that as our destination. We took a couple of wrong turns, backtracked a bit and found a more promising path to the stupa. We basically were walking along a grid of narrow foot paths between the squares of rice fields. To adjust our trajectory we would make right angle turns to pull us one square closer to the stupa. It made slow progress this way, which was fine, and slowly sunk deeper into the lush green of the rice. As distance from the road and houses increased sounds of people faded to faint wisps, replaced by the sound of the rice plants being combed by the breeze. It was beautiful, quiet and a welcome change from the clatter and squalor of the streets. The mountain that houses the Mahakala caves loomed far in the distance. It was the only piece of visible geographical relief around us.

This was where, years ago and way before the bridge, a few fellow students and I had hiked. We had waded through the monsoon-swollen Niranjana river to get there. It had been quite an adventure and had been a risk due to the banditry that was prevalent at that time (and may still be). Now we traversed the last field and reached the stupa. Perhaps it was the quiet, or because we had directed ourselves on our own feet that led me to find the stupa to be a more rewarding landmark than any temple than I visited upon returning to India. It seemed to me that the stupa was more of a monument to the beautiful, natural way of life around us than to Buddhism. It was very small and modest but well crafted. Apparently the Bhante of the Burmese Vihar had commissioned its construction. Then, while we stopped to pose for a few pictures. Then it happened- a woman that had been working in the rice fields approached and began a never-ending volley of requests for money.

The brief mystical spell I had been feeling dissipated quickly. Urged on by this and the heat, we turned and wandered on a bit. This time we chose to follow a road. It led further away from civilization and soon was just a rough dirt track that meandered through a grove of bamboo. Things got quieter- a little too quiet. A sinking feeling rose up and I reflected on Robert’s words so many years ago, to not wander the countryside. The feeling inspired me to insist that... perhaps we should head back in the direction we had come from. It seems the sommelier had the same idea. There are, of course, stories that banditry is alive and well in the countryside of Bihar. I did not want to test this and it seemed my fellow traveler didn't either. We turned to head back to the guesthouse. Within five or ten minutes we had dropped back down into the outer village. There we were met by a group of young men lounging beside the road.

They offered to sell us marijuana, which we politely declined. They then began and asking for money and, bizarrely… for chocolate. We told them the truth, that we didn’t have any money, or chocolate on us. We shrugged off the encounter and walked on a bit. The road forked and we chose to turn right. This led us directly down a densely developed residential section of the village. The homes were simple cubes plastered with a coffee-colored, mud finish. Here we were confronted with more assertive begging from some village children and with some glares from adults. The road led right through a gathering and we didn’t have much choice but to press on ahead. We sheepishly walked directly through the group of people along of them on the road. I remember greeting them with a clasp of hands and “Namaste.” The people kind of shrugged in response. They tolerated our passage but their dogs did not want to. There was much growling and posturing and baring of teeth.

Even I, a dedicated dog-guy, began to get worried. Bites would not be a good thing here. The threat of rabies meant immediate shots to the stomach with a large needle, if the medicine could even be procured let alone administered safely in our dusty locale. Slowly we inched past the dogs and the people and made it through to where the lane opened up and the houses relented. I heaved a big sigh of relief. Within a few minutes we were rounding the bend, threading through the buildings and coming into the guest house. Its' sense of safety was most welcome. I neglected to mention that it was hot- found myself in need of a drink, my clothing completely drenched with sweat. The sommelier and I parted ways to have a rest. I had not been in India too long at this point and the encounter with the dogs had shaken me. I made a mental note to look for a can of pepper spray in the bazar. I never did buy this as I figured doing this would be empowering fear and that carrying it on me might get me in trouble with the Indian Authorities. This was probably a good call.

For the next two weeks I lingered around town as my embellished memories gave way to what Bodh Gaya and India now were. The process worked in tandem with my adjustment to the culture, climate and land. Gradually I “came to” out of a fog of mysticism, idealism and embellished memories. It seems to me that Indians are very aware of the enchanting qualities of their land and incorporate that understanding for leverage in the tourist trade. The nature most businesses is the do this sort of thing. These operators have encountered hordes of spiritually hungry or entranced foreigners. It is completely understandable that operators would seek and find whatever leverage might be available to tap into the walking tourist resources. The operator's presentation can be dangerous to the visitor as they can become rendered blind by it. And it is a heartbreaking reality to crash out of a trance of spiritual tourism and realize that the deeply spiritual or heartfelt connection with your newfound “friends” is not as sincere as you had thought.

To provide an example, when I was initially received by Iz at the guesthouse I was in the thralls of a nostalgic trance for the Bodh Gaya I had left behind so long ago. In the time that followed I was given glimpses out of the cloud. Certain holes in Iz’s story surfaced. Then, with guilt at first, I began to question him and feel that I had given him too much of the benefit of the doubt. The initial experience of being asked for compensation for the windshield should have been a clear sign to me. Later on, while still under the spell of doing good through the guesthouse, I made the mistake of asking how I might do something nice for him and his wife. I was thinking of something along the lines of setting them up for a free dinner out at a nice restaurant, giving them a treat and a break from their daily grind. Iz responded by saying that boy they could really use a new washing machine. This seemed really inappropriate. Then, later, hints came that I could go into Gaya with them and help Iz’s wife pick out a nice piece of jewelry. Again came that sinking feeling.

Initially upon arriving I had been keen to rent a motorcycle. Iz had insisted that he had a spare Enfield at the guesthouse and that I was more than welcome to use it. I hesitated at this suggestion, feeling that it was too much for this overly giving man. But in time I grew tired of haggling for a decent price from the rickshaw drivers and tired of walking in the hot streets. So I inquired about the bike again. It took a number of days and conversations with Iz before it became clear that the bike was broken and needed about $800 in repairs. Iz kept insisting that “I could use it,” any time [after I paid to have it fixed]. Eight hundred dollars was more than a monthly travel budget for me. I was shocked when I finally understood the situation and offended with how Iz saw me. But it wasn't personal. I had a similar experience with a local who had befriended me on the streets. We visited a few restaurants where I treated him and his friend who would magically appear out of the woodwork. One day we were tooling around town after I bought us lunch.

Looking at the gas gauge of the motorcycle, the two guys reported that we had to stop for fuel. We drove way out of town. The farther out we drove the more a sinking feeling grew in my stomach. Finally we stopped at a gas station. They promptly asked me what I would contribute. At that moment I flashed on a moment when I had pulled my “pullout” wallet to pay for lunch. These dudes’ hungry eyes had lingered on the wallet too long. It was unsettling but I had brushed the feeling off. Now, at a petrol station on the outskirts of Bodh Gaya, the nature of things could not be clearer. I was a form of income for these men. For each stop, each restaurant, they had likely made a small commission. This truth hurt. I had foolishly thought that had friends in these people. But things were messed up. I informed them that I had just bought lunch and wasn’t going to contribute to fuel. I then asked to be returned to the temple where I permanently parted ways with them.

In each of the instances noted above there had been an artful skirting of the truth in a way that seemed much more sincere than similar efforts I had witnessed in the States. It really seemed that these people were sincere. But in each case, padding and pressure urging me in a direction based on a false presentation had been there all along. This was done solely for benefit of the presenters and their partners, of which I was the financier. I have experienced this in enough places I can only conclude that it is a business model especially abundant in developing countries. And it is one that is completely understandable, given the circumstances for many of these people. All this said for the tourist it can be a dangerous and devastating reality to wake up to. Given the number of foreign tourists present in India and the degree to which tourism is a part of the Indian economy, how many con jobs have transpired? Probably millions. This realization led to a catastrophic deflation of my idealistic view of India and the merits of life there as a foreigner. Somehow I had not seen this before ...or had blocked it from memory.

But now my heart was telling me otherwise. These were painful realizations and it was at this point that I became a harder and wiser traveler. I still slip sometimes and take what people are saying to me at face value. But usually this mistake reveals itself quite quickly and my education returns. With this also comes my understanding that as a traveler, I also must make less than sincere presentations simply for my own well being. While I am relating some difficult nuts and bolts of the traveling machine, there is another issue that I must address. I have spoken with other travelers and some Asian Americans in the States that have referred to a sort of colonial mentality that seeps into the minds of many people in former colonies of European world powers. I think it's mostly about classism and concern for the darkness of one’s skin. But there is more to it, I know that much.

One traveler that I met claimed that fear of the British due to trauma associated with the colonization and the tea industry made many modern day Indians, to this day, defer to British as if they are superior. The colonies have wrong horrible things, my own country being no exception. Anyways, I noticed an appeal some people have for association with Western visitors. I noticed that many people wanted to use me as an identity enhancer for themself. They wanted to be seen with me. They wanted to take selfies and video with me to post on social media. Many of these people would just hit the record button and stick their phone in my face and ask me to say something, as if I were a monkey or something. I found this extremely rude but understood that these folks had not been able to visit my home country, so this was the closest thing. Many seemed to want to show off their Californian surfer friend on social media in order to bolster their status. It was brutal to choose to trust people and have that responded to with attempts to use me.

>This further illustrated the severe cultural and socioeconomic divides between me and the land and people I was encountering. It often cleared the mists of any magical Indian cloud that I had gotten lost in. It had been an error to think that I could just waltz into this land and by sheer will of effort or political correctness bridge major cultural and socioeconomic divides. Travel can be done and experiences had but I don’t know that these divides can ever really be bridged. Unless you are Indian, no matter how hardcore your approach when you are visiting India, you are always doing so as the foreigner. And Indians that visit parts of their country far from home have reported to me similar experiences. Home culture is a relative term that can apply to one's vocation, village, faith, caste, gender, state, native language or any combination of these things.

>